- Home

- Hillary Carlip

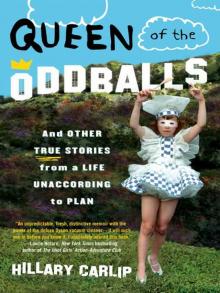

Queen of the Oddballs

Queen of the Oddballs Read online

Queen of the Oddballs

And Other True Stories from a Life Unaccording to Plan

Hillary Carlip

For Mom, Dad, and Bro, who made me everything I am today.

And for Mackie, who loves everything I am today.

Contents

Hilly Golightly

Mrs. Paul Henreid’s Trrophhhy Baaallll

They’re Very Loyal Fans, and They Bake

The King Case

Teen Libber

(Heart) Breaking News

Adventures of a Teenage Woman Juggler

Queen of the Oddballs

Dear Olivia Newton-John

Jack Haley Jr.’s Coat Closet

Anyone Can Be a Rock Star, or How to Be an Imposter

The Case of the Inexplicable Birthday Treasure Hunt

Tyro Scribes Sell Spec for Big Bucks

Madame Zola, Psychic to the Stars

Life, Death, and My Soap Opera Girlfriend

Vespas, Vespas, All Fall Down

Leaving Las Vegas…Please!

Finding the OH! in Oprah

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

1965

“The Name Game,” sung by Shirley Ellis, hits # 3 on the charts. Everyone sings their own name in the song but I sing “Chuck.” “Chuck Chuck Bo Buck Bonana-Fana Fo Fuck!!” Tee hee. (All right, I’m only eight years old.)

Months after Malcolm X is assassinated and Martin Luther King Jr. leads a march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, demanding voting rights for blacks, the Watts Riots erupt during a routine traffic stop. The rioting lasts for six days and requires 14,000 National Guardsmen to be called. I watch on our black-and-white television to make sure my black friend, Pat Wallace, is not one of the 4,000 people arrested or thirty-four killed.

A babysitter takes my brother and me to the Hollywood Bowl to see the Beatles LIVE IN CONCERT! I wear a fab Carnaby Street outfit—short print miniskirt with matching tie and cap, and purple windowpane stockings—and scream with all the other screaming fans throughout the entire concert.

See Miss Jane Hathaway from The Beverly Hillbillies buying meatballs at the Bel Air Market down the street from our house.

Just a few months before they score their first #1 hit song in America, “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” the Rolling Stones are arrested in London for public urination. Every time I hear Bob Dylan’s new song, “Like a Rolling Stone,” I get the urge to pee.

Go see my fave new movie, What’s New Pussycat?, two less times than my mother sees her fave new movie, The Sound of Music (me, four; Mom, six).

A Charlie Brown Christmas is broadcast on TV for the first time. I ask my parents when they’ll air A Charlie Brown Chanukah.

The Beatles perform on the Ed Sullivan Show. I try to photograph them, but when the pics are developed, all you can see is a big glare where the TV set was, and my brother’s feet in the frame.

Hilly Golightly

What do you do when you feel so invisible you can’t sleep without a light on, afraid that in the dark you just might vanish entirely? Simple. Become someone interesting enough to be noticed. And that’s exactly what I did when I was eight years old.

I took on different personas the way other kids tried on clothes. I Frugged and Mashed Potatoed incessantly for an entire month when I was being a go-go dancer from Hullabaloo! After that, for several weeks I yanked my short hair into pigtails, wore all black, and skulked around the house and school, acting “creepy, kooky, mysterious, and spooky,” when I was being Wednesday from The Addams Family. A few months later, hooked on Gerry and the Pacemakers, I sang and spoke only in an English accent. How much more interesting could I get?

The answer came one night when my parents were out and my ten-year-old brother, our teenage babysitter, and I watched the movie Breakfast at Tiffany’s on TV. I was smitten with Holly Golightly. Daring and darling, she shoplifted and had only one friend, her cat named Cat. She was strong and independent, saying things like “You don’t have to worry. I’ve taken care of myself for a long time.” Those words rang so true to me.

My parents, Mim and Bob, both on the short side, each with open, reassuring expressions and sympathetic smiles, took on full-time jobs as compassionate listeners to everyone else’s problems—the gardener’s, the grocery checkout clerk’s, the mailman’s. In fact on more than one occasion, they invited our mailman, Felix, to join us for dinner at the end of his route. They helped the neighbor’s daughter get into private school, found a job for the pharmacist’s son, and took in Esperanza, a teenage boarder from Guatemala. Whatever remained of my parents’ energy was sucked up by my hyperactive, rebellious older brother, Howard, whose constant demands for attention began as early as when, at six months old, he literally threw himself out of his crib.

I was definitely noticed when I started acting like Holly Golightly. Unfortunately, it wasn’t quite the sort of attention I had desired.

I sat on a hard wooden chair in the principal’s office, my arms hidden behind my back, when my parents walked in.

Mr. Shelton, the principal at Bellagio Road Elementary School, sported a head of bushy gray hair and matching moustache, making him look like Larry Tate from Bewitched. I wished I could twitch my nose like Samantha Stephens and turn myself into something tiny and unnoticeable, like a postage stamp.

“Your daughter’s being suspended from school,” he told my parents.

“From the third grade? Why?” My mother was stunned.

“What did she do?” my dad asked.

“Her teacher, Mrs. Renzoli, caught her on the playground smoking cigarettes.”

“What?” My mother shrieked as my dad’s eyes darted around, searching for an ashtray to stub out his Benson and Hedges.

“Hill, why were you smoking?” Mom asked.

I shrugged. My dad excused himself, opened the office door, stomped out his cigarette on the sidewalk right outside, then hurried back in. “Answer your mother,” he said.

I slowly pulled my arms from behind my back, revealing my mom’s black, elbow-length gloves that, on me, went up to my shoulders. “I was being Holly Golightly.”

“Who?” Mr. Shelton asked. It figured he didn’t know who she was.

“She’s a character from Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” my mother responded. “Hillary saw the movie recently, and I guess it made an impression.”

“I tried to get a long cigarette holder, but I couldn’t find one anywhere,” I said, confident in that moment that my parents were now on my side, having to explain to the ignorant principal who Holly Golightly was.

But they weren’t at all on my side. In fact, my latest shenanigans not only got me suspended, they also resulted in my being sent to Dr. Eleanor Troupe, Child Psychologist.

“Please, Mom, don’t make me go,” I begged at the door of Dr. Troupe’s office, a fading salmon pink one-story duplex dwarfed into near oblivion by the high-rises on busy Wilshire Boulevard in Westwood Village. “I’ll do anything you want if I don’t have to go—name it.”

My mother took a deep breath and exhaled any doubts she may have had. “Sorry, Hill. Your father and I have made our decision, and it’s final.”

We stepped into a waiting room, and I begrudgingly sat on the sofa—but it was difficult to maintain an attitude with my 3'10'' body swallowed up by puffy pink pillows.

Dr. Troupe came out to greet us, and the sight made me gasp out loud: a woman older than my grandmother, her body was distorted in several directions at once. She limped in on her left leg, which was bent to the right, while her torso twisted in the opposite direction. Her right hand looked like a claw, raised in

a permanent fist near her shoulder, and her mouth warped to the left, creating a bucktoothed, snarly smile.

“You must be Hillary,” she sputtered. “I’ve heard a lot about you, and you sound like a very interesting young lady. I’m very happy to meet you.”

Though I was terrified by her deformities, this was the first time anyone had called me interesting. That was enough for me to willingly follow her into her office. She motioned with her eyes—the only uncrossed thing on her body—for me to sit in a maroon leather chair. My mother called out from the waiting room, “I’ll pick you up in an hour,” then left.

Dr. Troupe pointed with her claw to a large glass jar filled to the top with a mix of Brach’s chewy chocolate and caramel squares wrapped snugly in smooth plastic. “Help yourself,” she said.

I did as she opened a cupboard and pulled out a board game. “You ever play Clue?”

“Sure. I played a lot recently when I was being the Girl from U.N.C.L.E. Well, not the Girl from U.N.C.L.E.—that part’s already taken by Stefanie Powers, who plays her on TV.”

“I see. Is she a detective?” Dr. Troupe asked as she opened the box and clumsily spilled out the miniature lead pipe, rope, revolver, and candlestick.

“Yep. For my birthday I got a Sixfinger spy kit.” I told her all about the plastic, flesh-colored extra finger that shot cap bombs, SOS flares, and message missiles and had a hidden clicker so I could communicate in code with anyone who understood the secret language.

“Fascinating. So who do you click messages with?”

“Uh, no one I know understands the secret language. So, nobody.”

Dr. Troupe chuckled and winked at me—at least it looked like she did.

“Well, then, who do you want to be?”

I felt my cheeks grow hot. I didn’t know how to answer her question.

“I’ll be Miss Scarlet,” she announced.

Phew. She meant in the game. Okay. “I’ll be Colonel Mustard.”

“Good choice.” She smiled her twisted smile right at me and handed me the dark yellow game piece. As we played Clue, Dr. Troupe casually asked me all sorts of questions. “What do like doing most in school?” “Do you have any hobbies?” “What’s your dog’s name?” After I took a secret passage from the study, I announced that Mrs. Peacock had used the lead pipe in the conservatory, and I won the game. Dr. Troupe squealed in delight. Usually when I won at home Howard would sit on my chest, pin me down, and torture me by letting out a long line of drool, trying to suck up the saliva before it dripped into my face—sometimes succeeding, more often not. I liked Dr. Troupe.

Then she looked at her watch. “I want to ask you one more thing,” she said. “Why do you think you’re here?”

I shrugged. “My teacher, Mrs. Renzoli, turned me in. She doesn’t like me much.”

“Why would you say that?”

“She’s always telling me to keep quiet, settle down.” I paused, then added, “I guess I don’t like her much, either. She has a pointy nose and wears a long black coat, so she looks like an old crow.”

Dr. Troupe laughed heartily.

“Well, I guess it’s really my parents’ fault. They’re the ones who made me come.”

“You know they sent you here because they care about you, don’t you?”

I wiped my bangs to the side of my forehead, as if making room for the thought to sink in.

“Well, our time is up today,” Dr. Troupe said, “but we’ll talk more about this next week. I look forward to seeing you Thursday.”

To my surprise, I looked forward to seeing her, too.

I visited Dr. Troupe weekly. We chatted while we played Lie Detector, Sorry, Careers, and Operation, which was a bit challenging for her as she tried to remove the patient’s “funny bone” with her clawed hand without setting off the buzzer. Her questions always turned out to be compliments. “Why do you think your parents wouldn’t love a neat kid like you?” “Do you have a lot of friends? You must.” “Why do you want to be other people when you’re such a fascinating young lady yourself?”

One late afternoon, two months into our sessions, I was in the car on the way to my appointment when my mother announced that this would be my last visit.

“Why? Why can’t I keep seeing Dr. Troupe?” I cried.

“She says you’re fine.”

“So? She’s my friend.” I wiped my nose on the sleeve of my Snoopy sweatshirt.

“We hired her to help you, and she said she’s done all she can.”

When my mother pulled up to the fading duplex, I stepped out of the car and slammed the door. My mom leaned over and rolled down the window. “Sorry, Hill.”

I tried to be brave. I cried only once during the whole session, and it wasn’t even when I lost a round of Parcheesi. The hour passed, and we said good-bye. Dr. Troupe bent over, even more than she already was, and she hugged me with her one good arm. She whispered in my ear, “Just try being yourself. I think you’re gonna like what you see. I know I do.”

For days after that last visit I refused to leave my bedroom. I was heartbroken over losing the only person who seemed interested in me. Besides, I planned to try and follow her advice to just be myself, but first I had to practice in private. Over the next few weeks, despite my urges, I didn’t take on any new personas. One night at the dinner table, I excitedly told my parents the good news of the day. “Mrs. Renzoli made me Blind Monitor!”

“Ya mean you watch the blind kids in your class?” Howard teased.

“Very funny.” I continued, “A bunch of times during the day I open and close the Venetian blinds. In the morning, before the class arrives, I open all the blinds that cover the windows on two walls. At rest time I close them, then reopen them fifteen minutes later, then close them again at the end of each day. If we see a film, I get to open and close them two more times and—”

“Okay, Hill. That’s great,” my father said.

“But I’m not done—”

“We get it. You’re on another talkathon. Can’t I have some quiet when I get home after a long day at work?”

My brother laughed. I lifted a glazed carrot coin from my plate and threw it at him. He scooped up a spoonful of mashed potatoes and flung them at me.

My father’s bottom lip began to curl. “Both of you go to your rooms. NOW!”

“Fine,” I snapped, throwing my napkin on the table. “I might as well be alone. Nobody listens to me anyway.” I stormed past my mother, who sighed heavily.

Later, when everyone was in bed, I sneaked downstairs and turned on the little black-and-white TV in the den. The movie Pollyanna was on. Hayley Mills starred as the optimistic and inquisitive orphan who sneaks out of her second-story window to attend a carnival and falls out of a tree, seriously hurting her leg. The whole town rallies, sending flowers and showering her with attention.

The next morning I put on a short, plaid dress, went to school, and colored my knee with an Indian red crayon. All day long I limped dramatically, due to my “injury,” and almost every classmate asked me what happened. “Fell out of a tree,” I sighed bravely.

At 3:00, as I was lowering the blinds, Mrs. Renzoli crowed, “Hillary, stay after class, please.”

I was scared she was going to send me to the principal’s office again, but when I remembered my punishment last time—Dr. Eleanor Troupe—I actually got excited. Maybe I’d be able to see my misshapen friend once more and eat caramels and play games and talk as much as I wanted to.

“Just go to your seat, kid,” Mrs. Renzoli said without looking up from her desk. She called everyone “kid.” She sat grading spelling tests. I knew I had misspelled “ukulele,” but I couldn’t possibly be getting in trouble for that, could I? A few minutes later, my mother arrived. This was unusual, as I always rode the school bus home.

“So,” she asked, “what’s Hillary done now?”

Mrs. Renzoli stood up and rearranged her long black coat, aligning the buttons that had strayed to the side. “Don’t

worry, Mrs. Carlip. This time I have good news. Out of all the students here at Bellagio Road Elementary School, the faculty has chosen your daughter to appear on the CBS television show Art Linkletter’s House Party.”

“What?” I called out. “Me on TV?”

My mother beamed.

“Your daughter’s quite a character,” Mrs. Renzoli said.

As my television debut approached, I began to feel deliriously happy. Now for sure I’d be interesting and worthy of attention. Every afternoon I watched kids saying “the darndest things” on Art Linkletter’s House Party and eagerly waited for my turn.

Finally, on a humid Thursday morning during summer vacation, my mother and brother dropped me off at an empty Bellagio Road Elementary School. I wished someone other than Mrs. Renzoli was around to witness the long, black stretch limousine parked in front, ready to whisk us off to CBS Studios, but my disappointment didn’t last long. I leaped into the back, careful not to wrinkle the simple, sleeveless yellow-and-white striped shirt my parents had picked out at Bullocks department store for me to wear. I straightened the white Peter Pan collar and retied the bouncy bow that sat on my left hip. I felt carefree and sassy.

Queen of the Oddballs

Queen of the Oddballs Find Me I'm Yours

Find Me I'm Yours